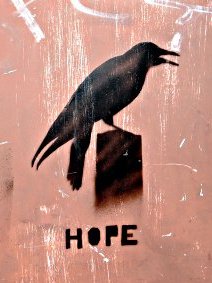

But for my children, I would have them keep their distance from the thickening center; corruption

Never has been compulsory, when the cities lie at the monster’s feet there are left the mountains.

-Robinson Jeffers

I left Calumet on a warm early October evening, riding the caboose of an ore train through the copper hills of upper Michigan, down to the Portage and a packet schooner bound for Ashland and Superior. My one friend Eino was the fireman onboard and would be glad for a little company and a younger back under the coal. There was a softness in the air that night, a feeling so suspicious after the first bracing nights of fall. Once you have given in to that next layer, it’s tough to let down your guard, but I was steaming up under my canvas coat and new woolens.

That rattly engine room would be plenty warm on the trip west. I had taken the trip twice before for a few dollars at times when Eino’s children were being born in Houghton. My first trip, the engineer had burst a can of oil all over the piping hot engine just before we left, and I spent the first six hours flustered and sick from the fumes in a four-foot roll abeam. I scrambled to keep up with the demands of the throttle above, but the schooner itself was happy as a cork. I thought that was it for me, sick and exhausted, but the engineer spelled me up through the Apostles and past the red cliffs, and I got some fresh air and salt herring in me. I guess they felt pity for my weakness.

This time I was going away on that boat. I had been laid off two months from any work and was in receivership at the boarding house. Pekka said she’d advance me another month but I’d had it with digging anyway. I knew a guy ran a skiff out of Tofte, a real upright norske I had met in Bergen on the boat from Europe. He was heading back to Minnesota, having worked the logging camps up above the mills at Cloquet for three winters. He’d made a stake, enough to come home and get a wife and buy a fishhouse cove on the Lake Superior. He had written once about trouble finding hands up there when the ciscoes started to shoal and he had more heaps of rotting fish than he could pack. That was my destination.

The train pulled into Hancock and I skipped down to the schooner, and soon we headed out on the big lake. The breeze that night! Offshore, just as soft as could be, smelling of every fresh pine stump in northern Wisconsin. I took turns with Eino going up on deck and watching the sun slant into the horizon as we came around the point into Chequamagon Bay. The Ashland docks had those electric lights since my last trip, cold jewels on the horizon that got fatter as we approached. A few moths still flew about, even in October, and they haloed those lights like crazies. The brightening was just getting started then. But that’s all I see at night nowadays, a century later, brightness. It’s all been laid bare to me.

We passed inside of Sand Island and motored easily up to the head of the lake, the breeze coming around to the east and quartering off the stern. It was fast sailing to the entrance at Superior. The boys dropped me off on the Minnesota side, and I walked a mile along the beach toward Duluth before bedding down for the night. Talk about lights! The hillside to the west was like a forest ablaze. I figured this electricity would stick. Folks like a lot of light—from an early age, I had noticed that.

I woke up chilly in my bedroll. The wind had come around so it was off the lake and kicking spittle off the surf. That damned breeze was damp and cold, and had entered my neck, kinking it up to my right. So I watched, mostly, the waves run up the beach as I walked the miles west toward the Duluth entrance. That canal is only a stone’s throw wide, but we had to ferry across in those days before they put in that bridge with the lifting deck. On the far side, I missed my step thinking too much about my damned neck. I pitched forward, stepped ahead without a sense of where I was going, and my right leg went down over the edge of the barge just before it rode up against the pier.

The next few hours are cloudy, and I wish I could travel back there now and peer over my own shoulder and see who it was that tended to me and got me up the hill to the hospital, and who it was that stole my pack. My leg was busted bad, the femur twisted, shattered into strands was how the doctor described it. I never walked right again after that slip, when I finally walked at all. That old ache, the physical memory of something so sudden and violent, is something I do not miss.

I was laid up in the seaman’s home for three weeks before somebody managed to question whether I belonged there. They gave me a week to make a go, but kept me aglow on morphine and finding every day swell, and then slung me on a stretcher and dropped me over at a Finn Church on Michigan Street. They, in turn, farmed me out to a family of Lutherans up over the hill in Esko. Those Finn farmers hoped, for the down payment of a winter of charity, to get a summer’s work out of me.

It was a bad time, then. They bunked me up in their kitchen. Plenty of heat, always somebody to fetch a slab of bread, but never a moment to crack a fart or get the crust out of my nose until night. Women jabbering about this and that, every little nicety and meaningless, a lantern burning twenty hours a day. After a month the man and his boy got me out to the sauna, and I screamed twice so sudden and loud from the leg that the neighbors come over.

The nights were dark then, and long, and I learned to sleep through all sorts of commotion, which helped, because they preached, too, all the time. But it wasn’t all hosannas and tales of the ancients. They kept telling me about the farm and how they were so lucky to be a part of something they owned. They were dirt poor, hardly owned anything that came out of a catalog, and most of those were second hand. They got along alright, I guess, always had coffee. But I felt sorry for them.

The leg knit up by spring so that I could go outside on willow crutches that the boy built. The air was good, still days with the sun dashing off the deep snow and water droplets falling everywhere. The old woman taught me to knit, and I made up enough socks that I was still wearing them three years later in the logging camps. They had me chopping wood by the end of May, and I could manage a wheelbarrow by June.

They talked all summer about how much work it was to cut the hay quick in August when it was ready, and how I was looking more ready every day to swing a scythe, how I would be able to pivot on my good leg. Damn it to hell, they went on about that hay! I grabbed my coat after dinner one cool night in early August, thanked them for their hospitality, and walked up the road to Cloquet. They sent the boy after me, and I tried to wave him off, but he came up and handed me two dollars.

I knew that fall would be the right time for a start in the logging camps. The leg felt good, stiff as a tree trunk, but little pain until the end of the day. The limp was a problem though, something that would keep me out of work. I’d never hire a gimp like me, never did. But it wasn’t a problem anyway, because they were busy like moths around the mills, and all of the crew foremen were trolling the taverns for strong young men to stack lumber. I had a job by the end of the night, and two beers from a soused Suomi in trade for a pair of socks that I had made wrong. I made both transactions from a bar stool, never walked once until I left at midnight to go find a place to sleep.

I worked two weeks with them boys, told them I had a cramp at first until they saw that it didn’t matter, that I could pull my load. That Cloquet smelled bad, though. And so much sawdust in the air that I was sneezing all the time, quick surprise sneezes so loud they sometimes called me snusa. Two of the fellers on that crew were going up the river for the winter, said they’d vouch me onto a crew to build a new camp up in Brimson. Free tickets on the train and everything. We rode the Missabe grade up from Two Harbors, sledged a load of lumber four miles on deer trails, sometimes knee-deep in loon shit. The camp site was on a high bank above a clear lake, lots of sun, nice breeze to knock down the bugs. The pines towered to the horizons, so many and so thick that they had no branches up the first fifty feet. Those top guys what decided to send us here knew what they were doing.

Once we’d built the bunkhouse and cookhouse, I stayed on with the winter crew to start the cut. The cook left after two weeks when the crew threatened mutiny over his flapjacks. He made them all runny, with little spots of flour still inside, couldn’t get it right even under threat of amputation. I got the job by default, the foreman thinking my gimp was slowing me down. It was that or leave, he said. I was steamed at first, but had a pretty good knack for it and the pay was just the same.

I made the flapjacks the old way, with lots of potatoes, and the crew ate as many as I could make. It’s cold work in that country in January, out in the woods at first light, the little birds drumming past your ears light as snow. Those boys burned up everything you could feed them. I cut wood all day, always something thawing or steeping or boiling on the stove. The smells, I’ll say, were wonderful: salt pork boiling with carrots and potatoes, herring sizzling in butter with onions. The thought of those smells! Smells that reach down and will your stomach to growl. The raw yearning of hunger! I was snug in that job all winter, a stroke of luck.

All the more lucky because I had the key to the larder. There were still some Chipeways living their old ways on Bear Lake near the river back then, and I’d trade pork and butter for furs, at great advantage for it was a hard winter, even for this country. I had a stash so big by spring I could barely keep them hidden, especially from the damned squirrels. I sold the whole lot to that half-breed dog-runner Micmac for three hundred dollars before he sledded down to Duluth. Not a fair price, but I had to keep him quiet. No other way could I have done it.

And so it was that I established myself up the Cloquet valley. Three more years as a camp cook and I had a stake enough to start up a little tavern at the rail stop. From that point it was like shooting sparrows in a birdbath. A fair percentage of loggers were dependable to drink up all of their wages, and I cornered that market by building some drafty shacks out back where they could while away their worthless bachelor youth after exhausting their backs another season. After a few years, I snatched up some equipment and ran ‘em as crews of my own, and they paid me back every penny they earned. After meals, booze, and shelter I managed to keep some of those poor bastards in debt for six, seven years. I even sold ‘em socks, finally. Loyal to a fault, stupid drunks. I’d throw in a skimpy pine box in the end to get their carcass off my place and seal the deal.

Those big money fellers cut this country like mowing a field, and built hillside mansions in Duluth, all lit up like that. I did pretty well too by the time all of the big pines were gone, and I was staying put up here in the country. I bought up cutover highlands for a pittance, and sent my bastards out to plant stock in the summers. There was still enough timber left in pockets to make a buck in the winter, but the boom was over, and new folks were moving in. They were just like those Finn farmers back in Esko, starry-eyed dreamers hoping to carve out a farmstead on the edge of a spruce bog. For a narrow profit, I happily peddled some of the “improved” real estate I had recently gathered. These folks would want something more from me eventually. Whoever heard of a duchy without peasants?

Or a duchess. One such new peasant, a Tauno Maki recently of Tower where he had labored deep in the mines for six years, a man who had shipped out of Tromso for the Keweenaw back when I was just a sniveling whelp in Sweden, purchased a stumpy forty acres up in Toimi from me, and brought three grown daughters into the fold. Helmi, the oldest, was the apple of her mother’s eye and the salt on my hard-boiled eggs. She took the tavern by storm, demanding wallpaper and privies and niceties, but I’ll be the first to say she gave the place some staying power. Boys I had never seen came in just to watch her fish pickles out of a barrel.

We ran that roadhouse for fifty years, seen a lot come and go, before I left my brittle and frozen corpse beneath the snow on a cold, cold February day long ago. That’s why I’m this now, this wispy disembodied too brainy nothing. I’m still around to tell you a story.